Biking Malawi

Visiting most of the Village X projects via 1100km of backroads

Mar 22 - Apr 19, 2019 -- compiled by Jeff DePree

featured on jeffdepree.com

Visiting most of the Village X projects via 1100km of backroads

Mar 22 - Apr 19, 2019 -- compiled by Jeff DePree

featured on jeffdepree.com

What to Pack: I brought a 25L pack that ended up weighing about 15lbs before any food or water. This was a good size for strapping on a bike rack.

Comprehensive List: cheap Chinese pack off Amazon with giant mesh side pockets, Moto G6 Android with case, convertible pants with belt, collared long-sleeve quick-dry shirt (ExOfficio), running shoes, sandals, running shorts, t-shirt, ultralight sun hat, three pairs briefs, three pairs socks, gloves, balaclava, rain jacket, dry bag for laptop, Macbook Air, puffy, 1.5L water bottle, small dry bag with toilet paper, bike pump, camera with 28x zoom (never used but would’ve been nice for safaris), bike multi-tool, headlamp, usb cables (2 types), ultra-packable secondary daypack, plug adapters, sawyer filter with 1L bag, emergency bivy bag, old peanut butter jar (for snacks), inflatable pillow, multivitamins and malaria pills, sunscreen, sunglasses, sunglass holder, floss, toothbrush, toothpaste, deodorant, 2 pens, earplugs, headphones, paper clip (for removing sim cards), passport and yellow fever card. Wishlist: cycling gloves, helmet with visor, buff, power bank for recharging phone.

Bikes: Most Malawians ride Humbers (~$70), which are very heavy, single-speed Indian workhorses that have welded racks and can carry hundreds of pounds of goods or people. But most Humber riders are pushing them most of the time. If you want something you can actually ride on Malawi’s rough, hilly roads, you need to shell out a couple bucks extra and get a second-hand mountain bike. Bee Bikes and Africycle both sell decent police auction bikes from the US and UK for about $100. You can also buy some of the leftovers from the short-lived free-roaming bikeshare craze. It’s hard to find a decent helmet, so bring one from home, or if you have a small head, you can potentially buy one from Game, or ask for someone to materialize one for you, but these are usually quite grungy. People don’t seem to lock their bikes very much, but you can buy one from Limbe for about $1. There aren’t too many bike tools available, but you can find cheap wrenches at hardware stores. There are dedicated bike shops in Limbe, Zomba, and most other major towns. In Blantyre and larger villages, you can find hardware shops with smaller selections. Since I was hitting lots of bumpy roads with an expensive laptop in-tow, I bought a big piece of foam and cut it to my rack -- these are sold for two bucks at the obvious foam shops that show up in every non-trivial town.

Water: Outside of the cities, there’s no bottled water, and aside from the stuff that’s been boiled for tea, the stuff in the pitchers at restaurants or sold out of reused bottles from coolers is questionable for those who have recently arrived in Malawi. They often add bleach to the borehole water, but not always. But if you carry a filter, you can make use of the ubiquitous boreholes and you’ll likely never want for clean water. Some areas have taps supplied by the Water Board, which may be safe, but should usually be filtered. Some areas only have access to surface water, which you probably don’t want to drink even after filtering.

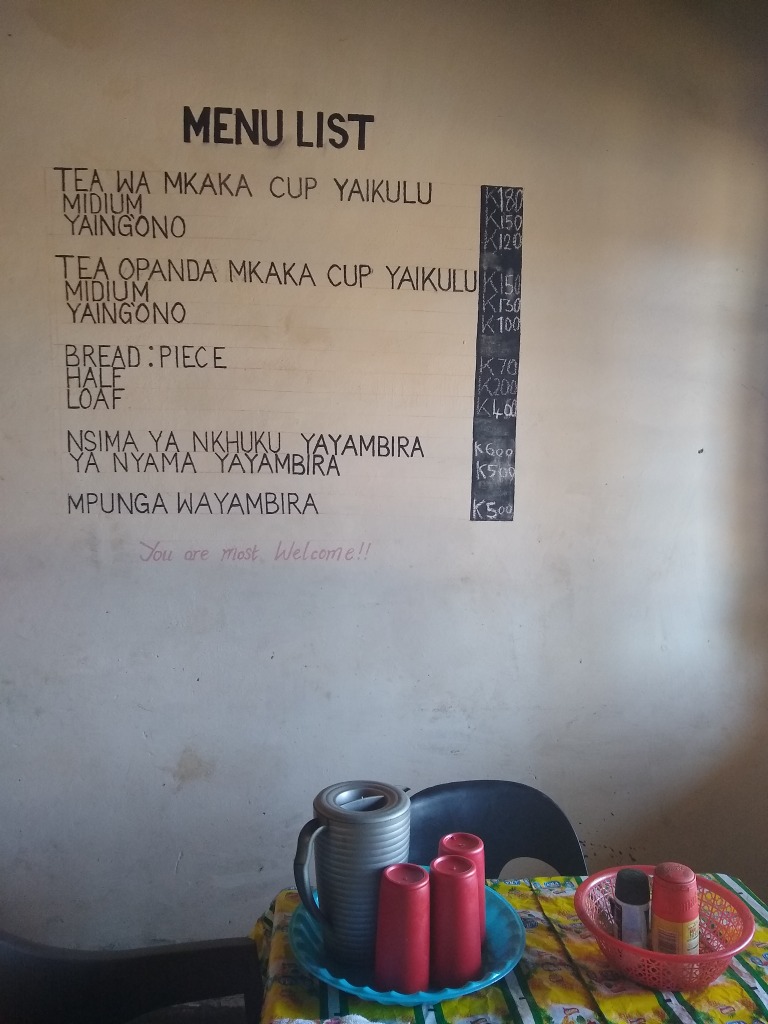

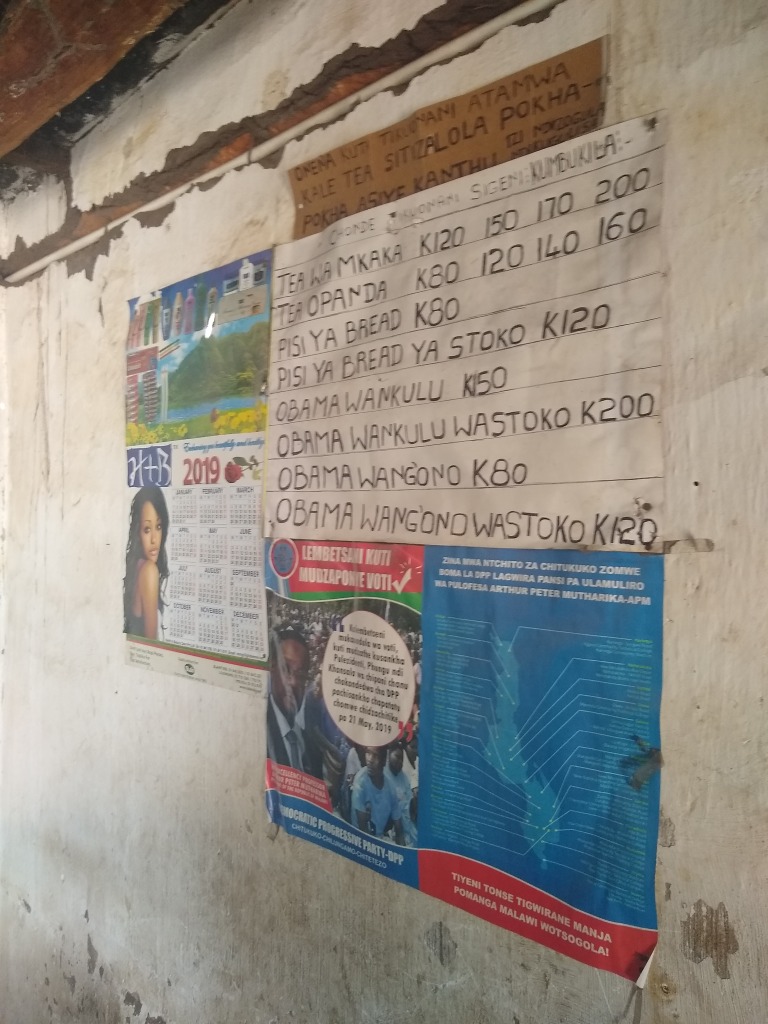

Food: Nutritious food can be hard to come by in rural areas. Buckets of donuts, samosas, and cornbread are nearly everywhere and always cost 7 cents. Stands serving up hot french fries and chicken are fairly common. Bread, UHT bags of milk, and sodas are available in the little groceries that appear in most villages. Restaurants only show up in major trading centers and are rarely open, but if you do manage to find one, you can often get rice or nsima with beans, stewed leaves, and/or parts of various animals that you never thought to eat. Nsima is a thick corn paste that forms a brick in your stomach and will leave you feeling full for many hours; there is a gooier variant in the north made from cassava. Most village food will include rocks that were not filtered out of the rice and greens, so chew gingerly.

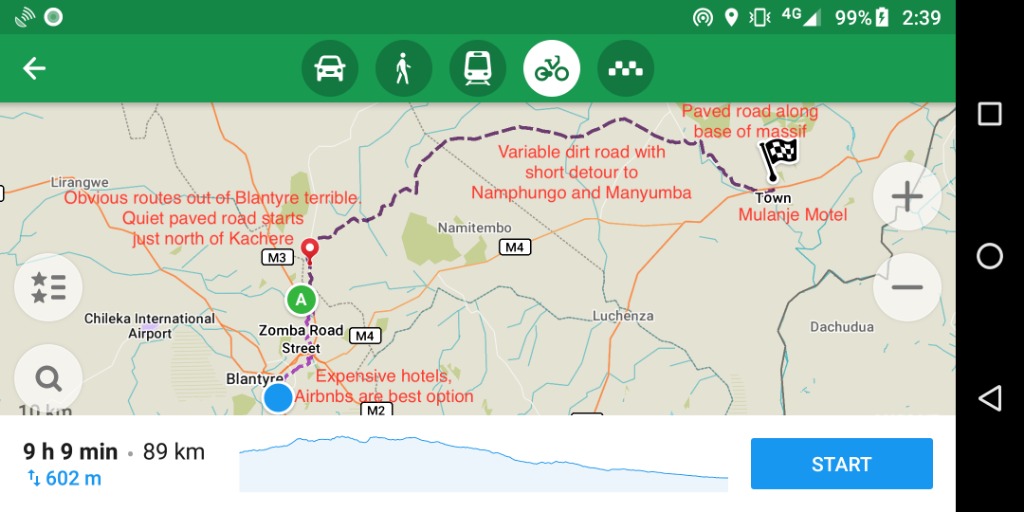

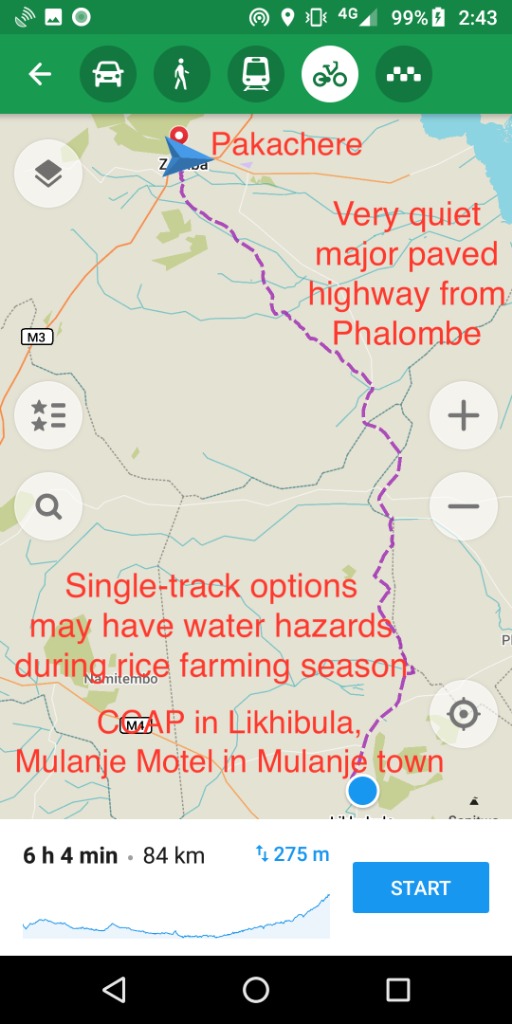

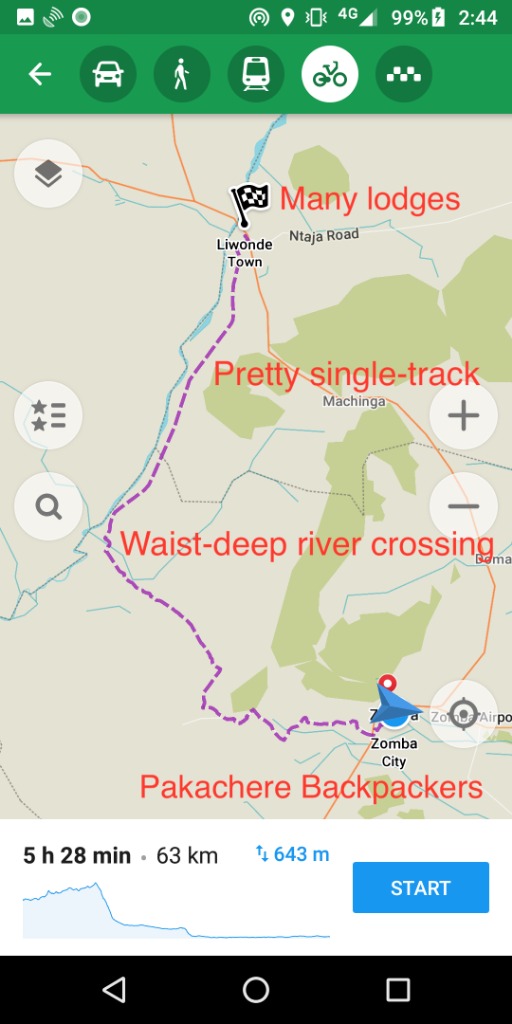

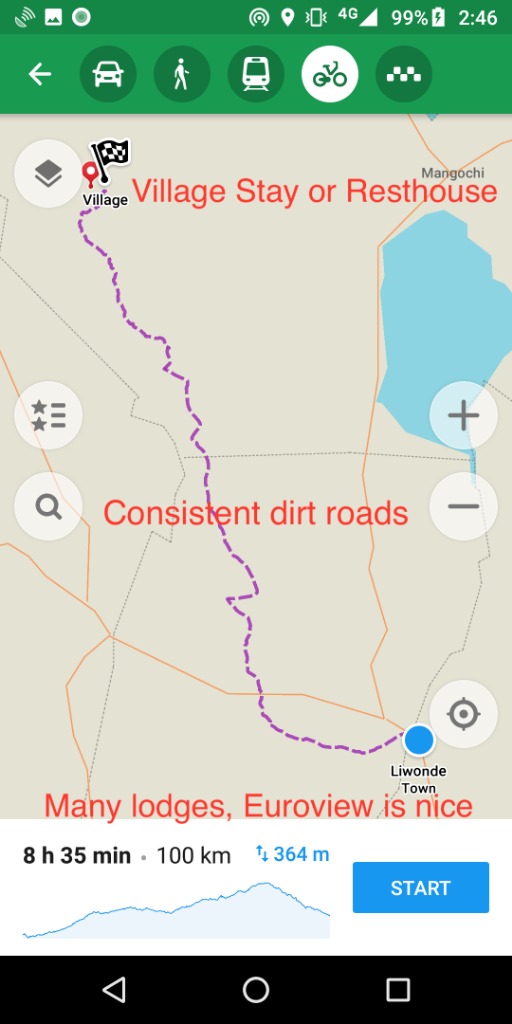

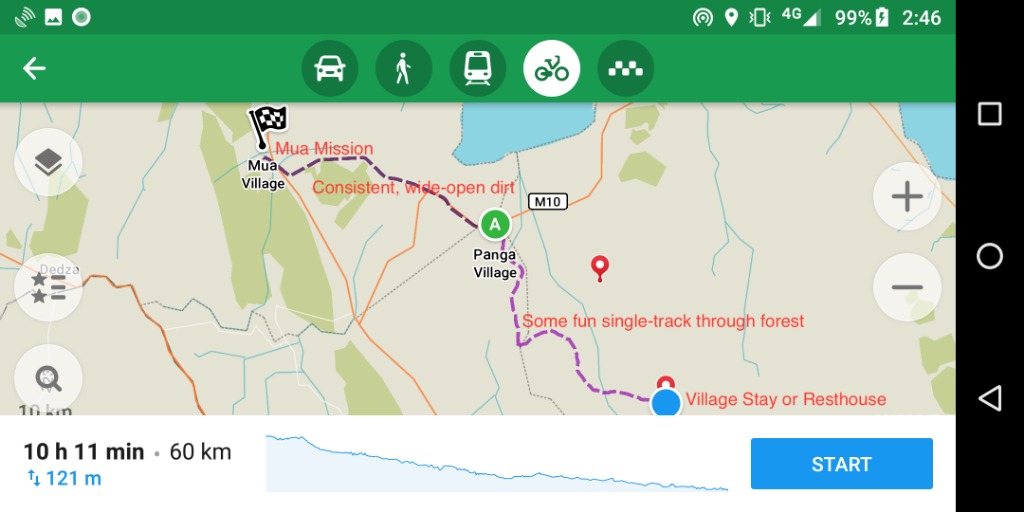

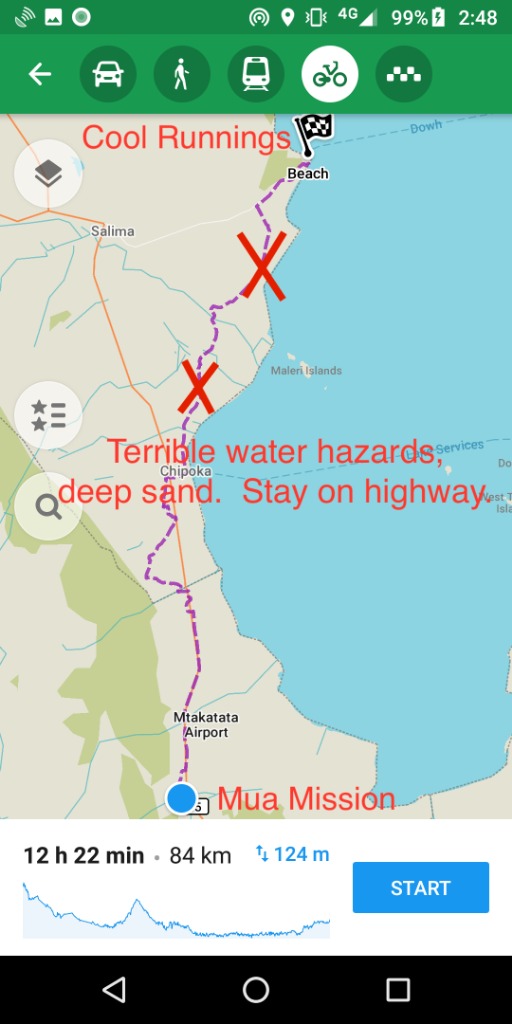

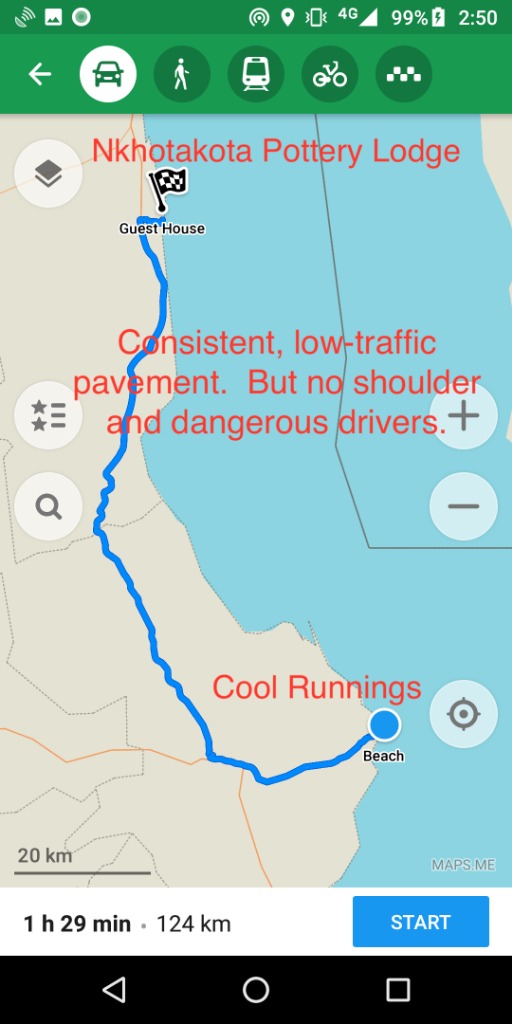

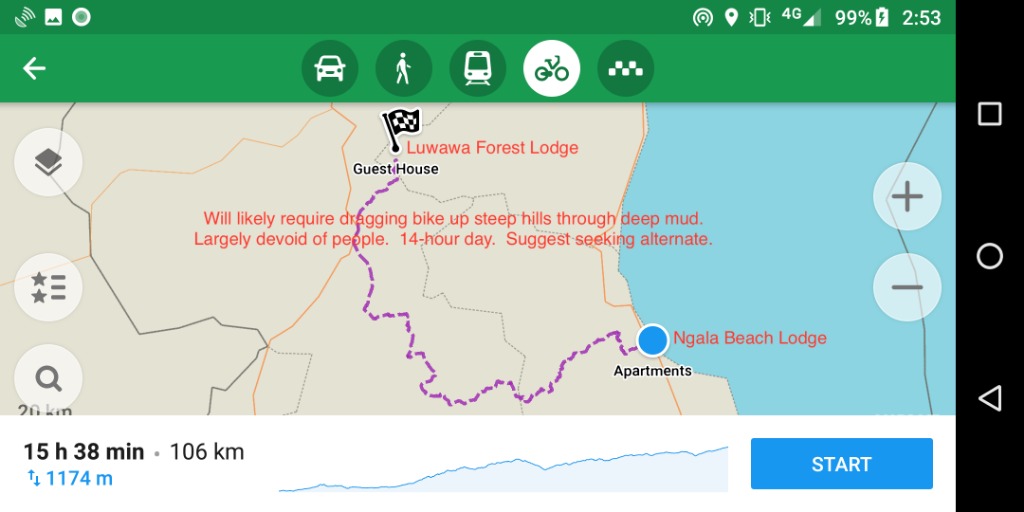

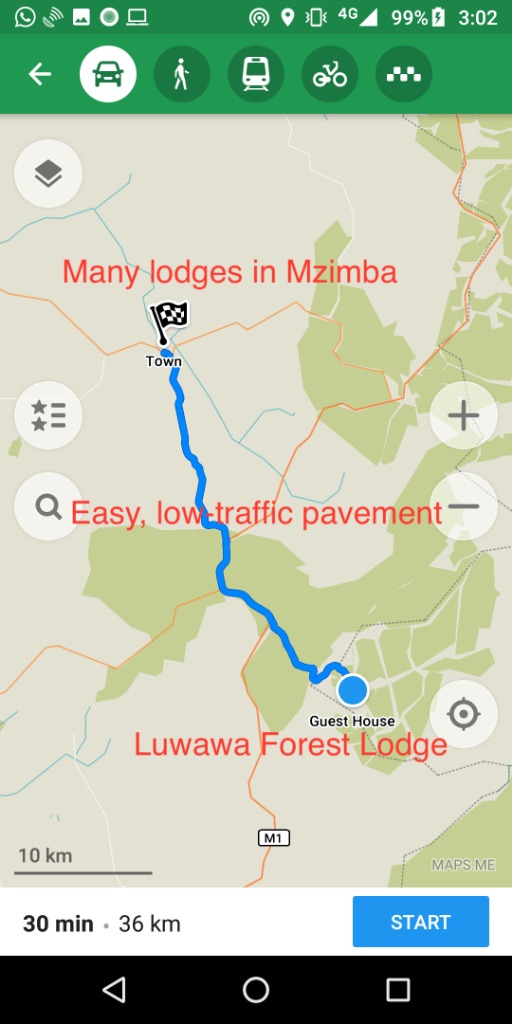

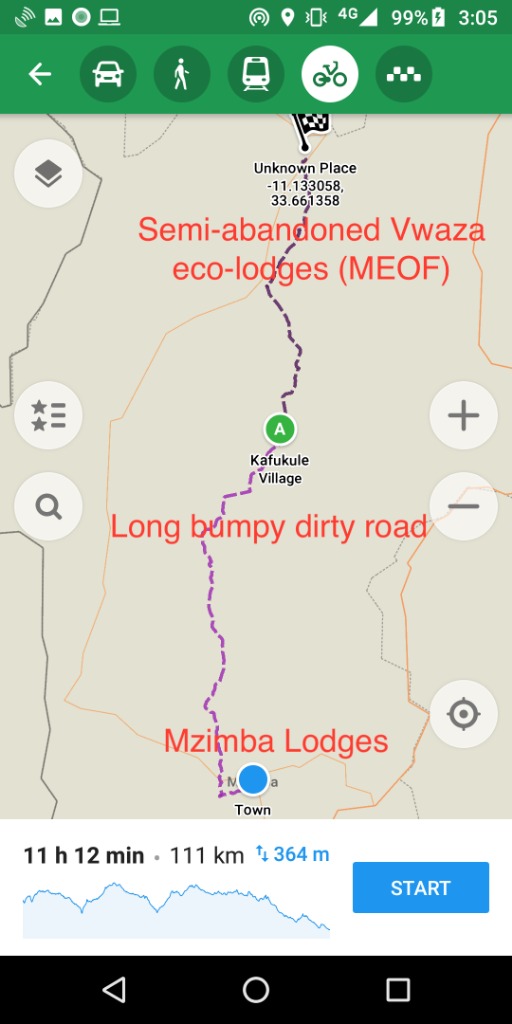

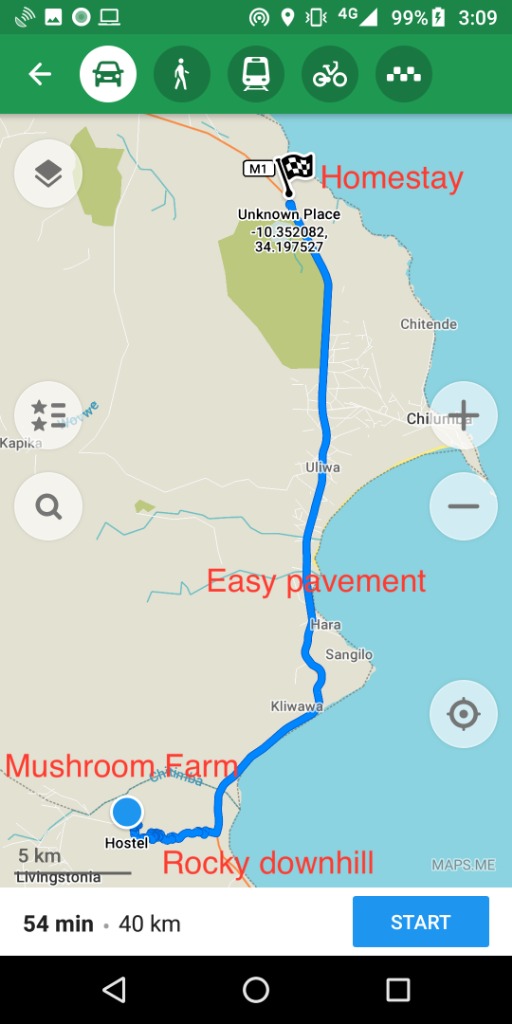

Navigation: OpenStreetMaps cycle directions are usually decent, but sometimes lead you to impassable rivers. MAPS.ME is one good offline mapping app. Sometimes the paved highways are quite empty and pleasant, but there are many quiet dirt roads and single-track that OSM will sometimes help you find. Most drivers in this country want to kill you, or are at least completely indifferent to running you over; it would not be a bad idea to jump off the pavement whenever you hear a car coming, and you should definitely do this if two cars are approaching at the same time.

Repairs: Unless it’s a Sunday, you’ll rarely have to walk too far to find a group of guys advertising themselves as bike mechanics. Most of these guys don’t have the know-how or tools to properly fix your bike, but they’ll do their best to fake it. Tire patches are usually fairly effective and cost 30 cents or 60 cents depending on your skin color. It’s advisable to pick up a wrench for your brake screws as the repair guys will likely strip them. Many of the repairs involve filing or other destructive, irreversible measures. One shop tried to fix my loose crank by hitting it with a very large rock. While not everything is available, some parts are quite cheap at most hardware stores; a knobby tire costs $7, an extra tube is $2, a bike rack, $3, and a set of brake pads, 70 cents.

Lodging: In Blantyre, AirBnb is likely the best option, as hotels are overpriced. But many hosts will bug bomb your room and then close all the windows, leaving you with rather toxic air. In other towns, there are lodges with private rooms for as low as $4, and the less fancy ones usually include breakfast. I found that most of the stuff below $10 didn’t meet western standards for cleanliness. Some villages have very inexpensive resthouses that I suspect could be a bit scary. Homestays in villages are often a good option and will likely be less than $3 with full board; the best way to find these is to ask around for the chief. Village stays are unlikely to offer electricity; they often have mosquito nets, but it might be a good idea to pack your own. Most of the fancier rural lodges offer camping to overlanders for $5-10 and dorms for $15. Lodges can be hard to find; Jumia is probably the best app for finding them, but there are many that don’t seem to be listed anywhere.

Internet: This is a difficult concept to grasp in today’s world, but Malawi has no free wifi. You will need to pay for every megabyte you use. But if you accept this early on, and shell out for a data pack of the appropriate size, you can still lead a pretty normal digital life here. Airtel has decently fast coverage pretty much everywhere and I’ve heard TNM is similar. I bought 15gb of data that was good for 30 days for around $26. This was adequate for most uses and allowed me to freely use internet wherever I went, without having to ever think about wifi. Most places offer something called Skyband and you can get 100mb for free each day if you login with Facebook or Google, but this is slow and a hassle, and will probably end up being more expensive, so just ignore it and use your phone. Make sure you bring an unlocked phone that supports swapping out sims and tethering.

Language: In most villages, you can find someone who speaks some amount of English. It’s useful to learn a few basic phrases in Chichewa, namely “How are you?” and “I am fine, and you?” -- regardless of the language you choose, 90% of your interactions will be comprised of exactly this exchange. It might also be nice to be able to ask how much something is, but everyone uses the English numbers, and in most cases, a seller will assume that this is the question you are asking and give you the price the second you point at anything.

Weather: It is difficult to comprehend the strength of the African sun. You should plan to cover every inch of your skin in light, breathable material. In the winter, the temperature is bearable and rain is infrequent, but you can still get hit by a devastating thunderstorm early in the dry season.

Safety: Malawi has an extremely dense rural population, so in most parts of the country, you’ll never be out of sight of multiple villagers, and it’s unlikely that anyone will give you trouble during the day. More caution is required in choosing routes through forests, where you can walk for hours and never see another person, and, I am told, encounter thieves and packs of rabid dogs. The cities aren’t particularly safe at night and are sometimes patrolled by packs of killer hyenas.

Villager Interactions: Most of the time, people are quite friendly, but many are extremely poor and I did feel a fair bit more resentment than I have in other places like Cambodia. Children will often wave and yell “mzungu” (white person). In some parts of the country, children and adults will yell “give me money”, or “give me bottle/pen/etc.”. On one occasion, small children chased after me and tried to pull my bottles and loaf of bread from my pack. One kid threw a rock at me, but he hit my arm and smiled as if he were just being playful; on many occasions, I noticed small children brandishing large knives, or other dangerous weapons, with maniacal looks in their eyes.

Health: In the wet season, malaria prophylaxis is probably a good call, but may be more trouble than it’s worth in the winter months. It might be a good idea to carry around a course of treatment and bring one home with you in case you come down with malaria and don’t have ready access to a clinic. Bilharzia and other parasitic infections are quite common, and if you go swimming or end up wading through rice paddies or streams, it could be a good idea to take the appropriate drugs proactively. Walking barefoot, even on the beach, is usually a bad idea.

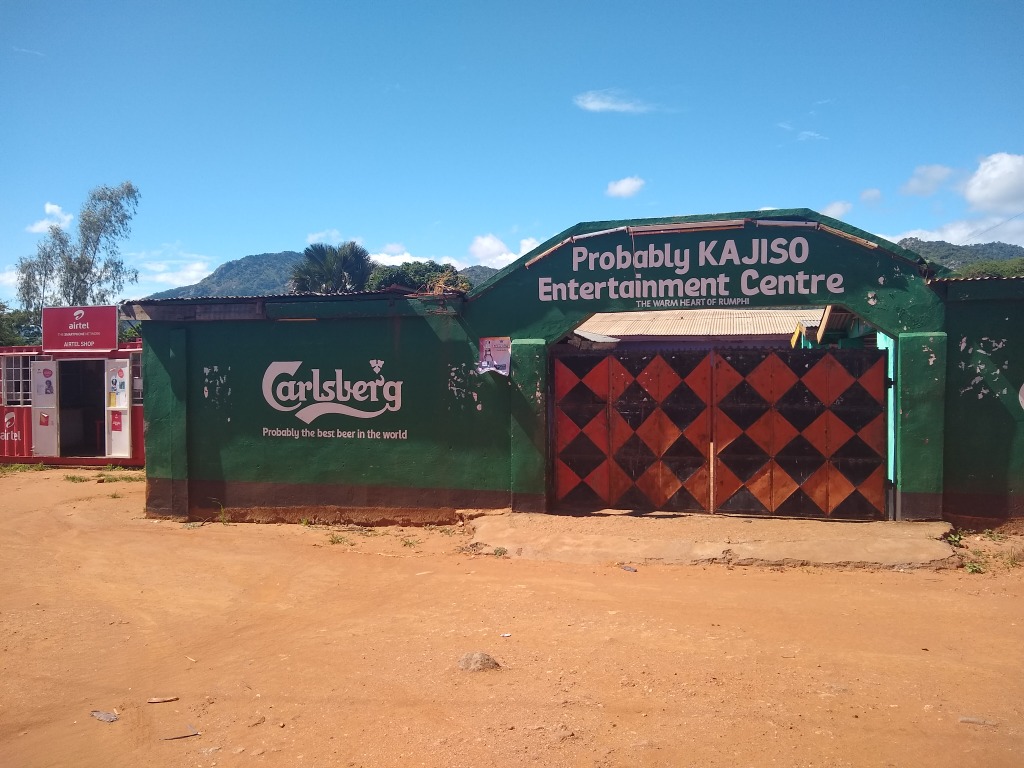

Beer: There is really only one beer company, but lucky for you, it’s “probably the best beer in the world” - they make 5 different beers which all cost about a dollar; some of the really fancy lodges charge $2. If that’s too pricey for you, you could try Chibuku Shake Shake, which is a sorghum-based beer that comes in a liter milk carton; the alcohol content changes over time, but it never gets much above 4; yet somehow, I never came across anyone drinking it that was even remotely coherent. I tried the chocolate variety of this one night; it cost about 80 cents for a liter and tasted a bit like cold vomit; most of the time, it will be the ambient temperature.

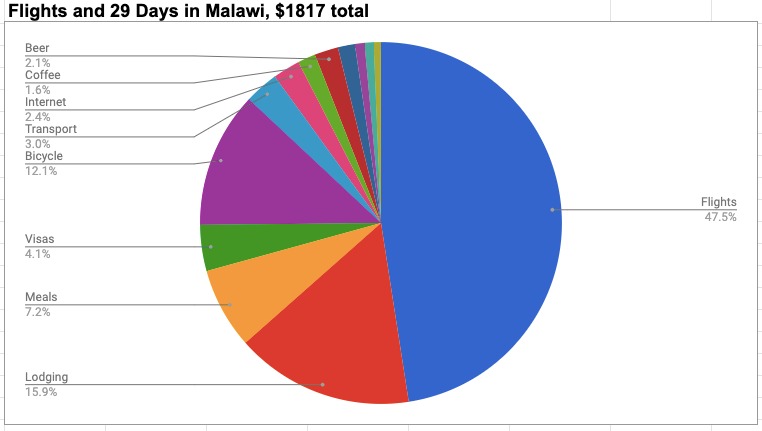

Costs: Unless you have really expensive tastes, your flight and visa will almost certainly make up the majority of your costs. If you stay in the villages, you’re unlikely to spend more than a few dollars a day. In the cities, you can live very well staying in clean lodges and eating food without rocks for around $20/day.

Trash: There are no trash cans here. Glass bottles have a deposit. Plastic bottles are in high-demand, so you can set one down wherever and someone will use it as a fishing bobber or resell it. For everything else, you’ll likely have to pack it out to the nearest city or throw it on the ground -- in general, you’ll have to come to terms with a novel worldview where trash doesn’t simply magically disappear.

Comprehensive List: cheap Chinese pack off Amazon with giant mesh side pockets, Moto G6 Android with case, convertible pants with belt, collared long-sleeve quick-dry shirt (ExOfficio), running shoes, sandals, running shorts, t-shirt, ultralight sun hat, three pairs briefs, three pairs socks, gloves, balaclava, rain jacket, dry bag for laptop, Macbook Air, puffy, 1.5L water bottle, small dry bag with toilet paper, bike pump, camera with 28x zoom (never used but would’ve been nice for safaris), bike multi-tool, headlamp, usb cables (2 types), ultra-packable secondary daypack, plug adapters, sawyer filter with 1L bag, emergency bivy bag, old peanut butter jar (for snacks), inflatable pillow, multivitamins and malaria pills, sunscreen, sunglasses, sunglass holder, floss, toothbrush, toothpaste, deodorant, 2 pens, earplugs, headphones, paper clip (for removing sim cards), passport and yellow fever card. Wishlist: cycling gloves, helmet with visor, buff, power bank for recharging phone.

Bikes: Most Malawians ride Humbers (~$70), which are very heavy, single-speed Indian workhorses that have welded racks and can carry hundreds of pounds of goods or people. But most Humber riders are pushing them most of the time. If you want something you can actually ride on Malawi’s rough, hilly roads, you need to shell out a couple bucks extra and get a second-hand mountain bike. Bee Bikes and Africycle both sell decent police auction bikes from the US and UK for about $100. You can also buy some of the leftovers from the short-lived free-roaming bikeshare craze. It’s hard to find a decent helmet, so bring one from home, or if you have a small head, you can potentially buy one from Game, or ask for someone to materialize one for you, but these are usually quite grungy. People don’t seem to lock their bikes very much, but you can buy one from Limbe for about $1. There aren’t too many bike tools available, but you can find cheap wrenches at hardware stores. There are dedicated bike shops in Limbe, Zomba, and most other major towns. In Blantyre and larger villages, you can find hardware shops with smaller selections. Since I was hitting lots of bumpy roads with an expensive laptop in-tow, I bought a big piece of foam and cut it to my rack -- these are sold for two bucks at the obvious foam shops that show up in every non-trivial town.

Water: Outside of the cities, there’s no bottled water, and aside from the stuff that’s been boiled for tea, the stuff in the pitchers at restaurants or sold out of reused bottles from coolers is questionable for those who have recently arrived in Malawi. They often add bleach to the borehole water, but not always. But if you carry a filter, you can make use of the ubiquitous boreholes and you’ll likely never want for clean water. Some areas have taps supplied by the Water Board, which may be safe, but should usually be filtered. Some areas only have access to surface water, which you probably don’t want to drink even after filtering.

Food: Nutritious food can be hard to come by in rural areas. Buckets of donuts, samosas, and cornbread are nearly everywhere and always cost 7 cents. Stands serving up hot french fries and chicken are fairly common. Bread, UHT bags of milk, and sodas are available in the little groceries that appear in most villages. Restaurants only show up in major trading centers and are rarely open, but if you do manage to find one, you can often get rice or nsima with beans, stewed leaves, and/or parts of various animals that you never thought to eat. Nsima is a thick corn paste that forms a brick in your stomach and will leave you feeling full for many hours; there is a gooier variant in the north made from cassava. Most village food will include rocks that were not filtered out of the rice and greens, so chew gingerly.

Navigation: OpenStreetMaps cycle directions are usually decent, but sometimes lead you to impassable rivers. MAPS.ME is one good offline mapping app. Sometimes the paved highways are quite empty and pleasant, but there are many quiet dirt roads and single-track that OSM will sometimes help you find. Most drivers in this country want to kill you, or are at least completely indifferent to running you over; it would not be a bad idea to jump off the pavement whenever you hear a car coming, and you should definitely do this if two cars are approaching at the same time.

Repairs: Unless it’s a Sunday, you’ll rarely have to walk too far to find a group of guys advertising themselves as bike mechanics. Most of these guys don’t have the know-how or tools to properly fix your bike, but they’ll do their best to fake it. Tire patches are usually fairly effective and cost 30 cents or 60 cents depending on your skin color. It’s advisable to pick up a wrench for your brake screws as the repair guys will likely strip them. Many of the repairs involve filing or other destructive, irreversible measures. One shop tried to fix my loose crank by hitting it with a very large rock. While not everything is available, some parts are quite cheap at most hardware stores; a knobby tire costs $7, an extra tube is $2, a bike rack, $3, and a set of brake pads, 70 cents.

Lodging: In Blantyre, AirBnb is likely the best option, as hotels are overpriced. But many hosts will bug bomb your room and then close all the windows, leaving you with rather toxic air. In other towns, there are lodges with private rooms for as low as $4, and the less fancy ones usually include breakfast. I found that most of the stuff below $10 didn’t meet western standards for cleanliness. Some villages have very inexpensive resthouses that I suspect could be a bit scary. Homestays in villages are often a good option and will likely be less than $3 with full board; the best way to find these is to ask around for the chief. Village stays are unlikely to offer electricity; they often have mosquito nets, but it might be a good idea to pack your own. Most of the fancier rural lodges offer camping to overlanders for $5-10 and dorms for $15. Lodges can be hard to find; Jumia is probably the best app for finding them, but there are many that don’t seem to be listed anywhere.

Internet: This is a difficult concept to grasp in today’s world, but Malawi has no free wifi. You will need to pay for every megabyte you use. But if you accept this early on, and shell out for a data pack of the appropriate size, you can still lead a pretty normal digital life here. Airtel has decently fast coverage pretty much everywhere and I’ve heard TNM is similar. I bought 15gb of data that was good for 30 days for around $26. This was adequate for most uses and allowed me to freely use internet wherever I went, without having to ever think about wifi. Most places offer something called Skyband and you can get 100mb for free each day if you login with Facebook or Google, but this is slow and a hassle, and will probably end up being more expensive, so just ignore it and use your phone. Make sure you bring an unlocked phone that supports swapping out sims and tethering.

Language: In most villages, you can find someone who speaks some amount of English. It’s useful to learn a few basic phrases in Chichewa, namely “How are you?” and “I am fine, and you?” -- regardless of the language you choose, 90% of your interactions will be comprised of exactly this exchange. It might also be nice to be able to ask how much something is, but everyone uses the English numbers, and in most cases, a seller will assume that this is the question you are asking and give you the price the second you point at anything.

Weather: It is difficult to comprehend the strength of the African sun. You should plan to cover every inch of your skin in light, breathable material. In the winter, the temperature is bearable and rain is infrequent, but you can still get hit by a devastating thunderstorm early in the dry season.

Safety: Malawi has an extremely dense rural population, so in most parts of the country, you’ll never be out of sight of multiple villagers, and it’s unlikely that anyone will give you trouble during the day. More caution is required in choosing routes through forests, where you can walk for hours and never see another person, and, I am told, encounter thieves and packs of rabid dogs. The cities aren’t particularly safe at night and are sometimes patrolled by packs of killer hyenas.

Villager Interactions: Most of the time, people are quite friendly, but many are extremely poor and I did feel a fair bit more resentment than I have in other places like Cambodia. Children will often wave and yell “mzungu” (white person). In some parts of the country, children and adults will yell “give me money”, or “give me bottle/pen/etc.”. On one occasion, small children chased after me and tried to pull my bottles and loaf of bread from my pack. One kid threw a rock at me, but he hit my arm and smiled as if he were just being playful; on many occasions, I noticed small children brandishing large knives, or other dangerous weapons, with maniacal looks in their eyes.

Health: In the wet season, malaria prophylaxis is probably a good call, but may be more trouble than it’s worth in the winter months. It might be a good idea to carry around a course of treatment and bring one home with you in case you come down with malaria and don’t have ready access to a clinic. Bilharzia and other parasitic infections are quite common, and if you go swimming or end up wading through rice paddies or streams, it could be a good idea to take the appropriate drugs proactively. Walking barefoot, even on the beach, is usually a bad idea.

Beer: There is really only one beer company, but lucky for you, it’s “probably the best beer in the world” - they make 5 different beers which all cost about a dollar; some of the really fancy lodges charge $2. If that’s too pricey for you, you could try Chibuku Shake Shake, which is a sorghum-based beer that comes in a liter milk carton; the alcohol content changes over time, but it never gets much above 4; yet somehow, I never came across anyone drinking it that was even remotely coherent. I tried the chocolate variety of this one night; it cost about 80 cents for a liter and tasted a bit like cold vomit; most of the time, it will be the ambient temperature.

Costs: Unless you have really expensive tastes, your flight and visa will almost certainly make up the majority of your costs. If you stay in the villages, you’re unlikely to spend more than a few dollars a day. In the cities, you can live very well staying in clean lodges and eating food without rocks for around $20/day.

Trash: There are no trash cans here. Glass bottles have a deposit. Plastic bottles are in high-demand, so you can set one down wherever and someone will use it as a fishing bobber or resell it. For everything else, you’ll likely have to pack it out to the nearest city or throw it on the ground -- in general, you’ll have to come to terms with a novel worldview where trash doesn’t simply magically disappear.

DC has a few more trees than Malawi

Odd development priorities

Nsima with greens and tiny fish - one of the less tasty things I've eaten in my life.

I had this romantic notion that I would ride the same heavy-duty Indian bike that all the locals used. Malawians across the economic spectrum found this hilarious.

Beans and leaves mixed with peanut butter are the most frequent veg options. Fried eggs are almost always available.

Real estate agent

Police auction bikes are shipped by the hundreds from the UK, then fixed up and sold to locals (and me) for $100 each, and the proceeds fund a local primary school.

Full-building homage to the wonder that is Doom.

My Airbnb had an armed guard, as well as a few less conventional security measures.

Bike 2.0, complete with foam-padded bike rack.

Pumpkin season is in full-swing, but I haven't found a single restaurant that will serve it to me.

Charcoal transport mechanism.

Tea houses are one of the few options for food and hydration in rural Malawi. You can get a cup with powdered milk and a pound of sugar accompanied by half a loaf of bread. Some locations also sell Obama's grandparents.

No one seems to lock up their bikes around here and I got flack for watching mine a little too closely.

Nary a car in sight.

A practical campaign promise: more corn!

Mulanje in the backyard

Tea plantations

Quiet market.

Poor vis on the way up.

Our deluxe mountain cabin

$1.25/night doesn't buy what it used to

Scarecrow guarding tree farm

On the way to Chambe Peak

Morning traffic

Navigating the rice paddies

Market fish stand

Water hazard

Fall colors

Getting some use out of the Mwanga borehole villagex.org/86

This was marketed as goat meat, but appeared to be clumps of goat skin bound with intestine.

One of countless amusing business names

Jemus nursery school awaiting the imminent descent of morning scholars villagex.org/140

After a few years of heavy use, the Saiti borehole is currently pumping out muddy water, but it is believed to be repairable. villagex.org/97

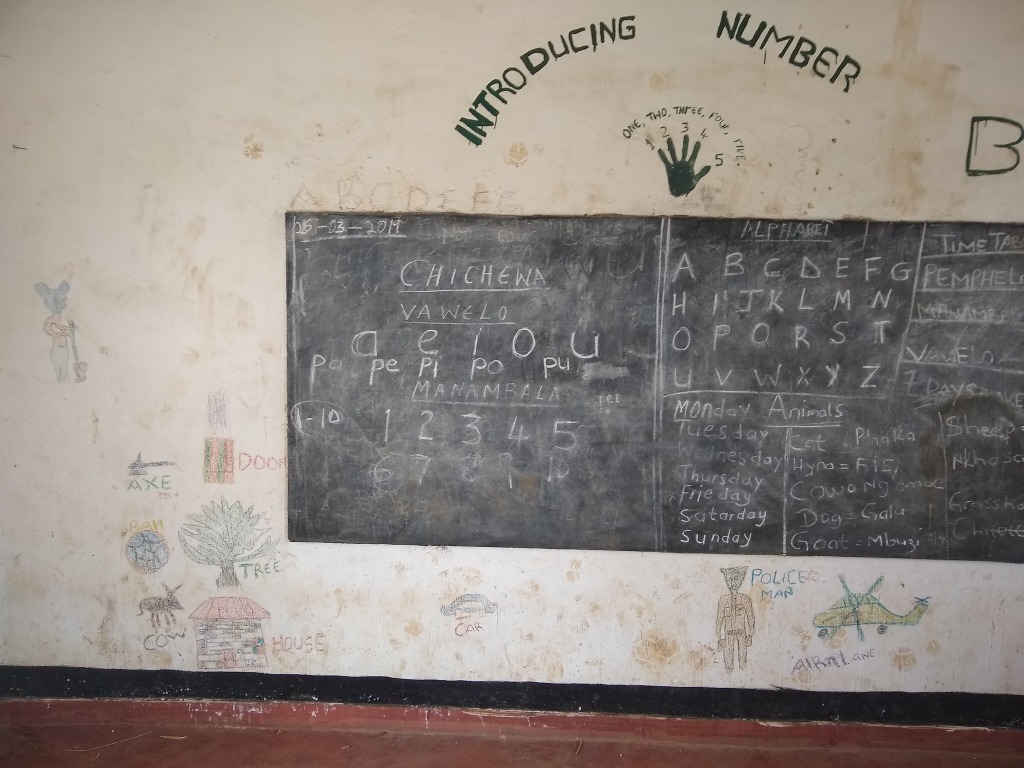

Excited students and teachers were in ready supply at each of the nursery schools.

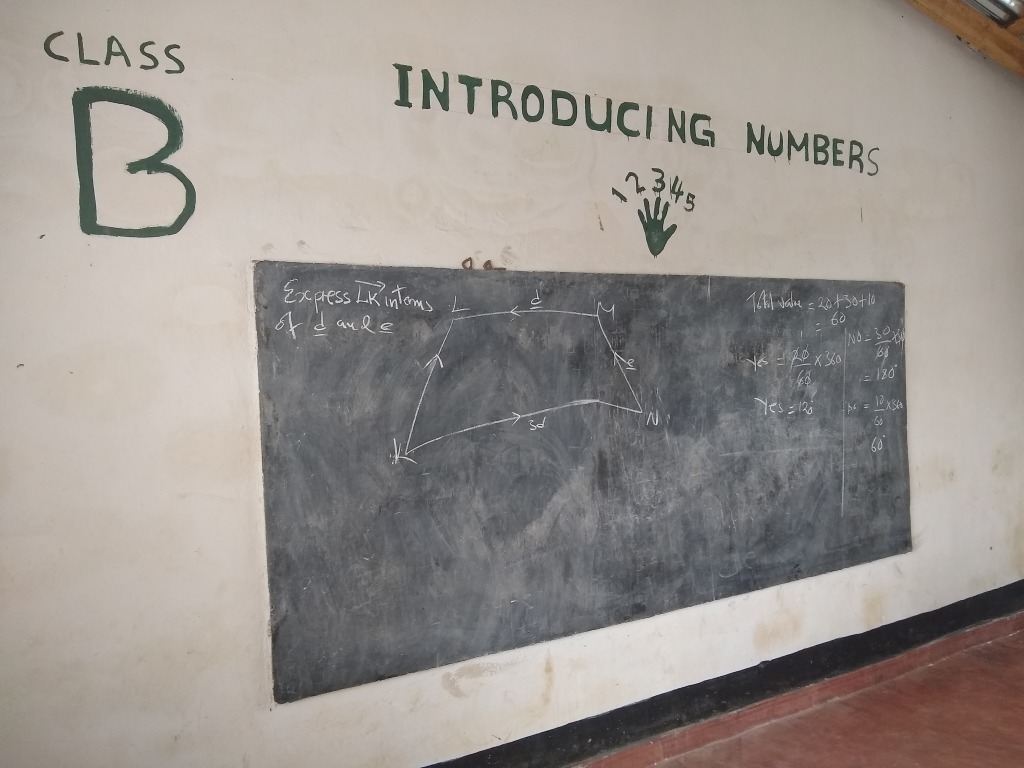

These overachieving nursery students have moved on to advanced trigonometry.

Performing "rain, rain, go away"

The Mlenga borehole, which I'm told was the first-ever Village X project, is still going strong. villagex.org/83

Fishing in the reservoir

Chipiri has no shortage of eager learners and teachers, but they could certainly benefit from a new school building.

Tackling the slickrock.

Biking through the trading center on a non-market day.

We could usually find a ready supply of pump models, but this borehole was surprisingly quiet.

Cyclone damage to baobab.

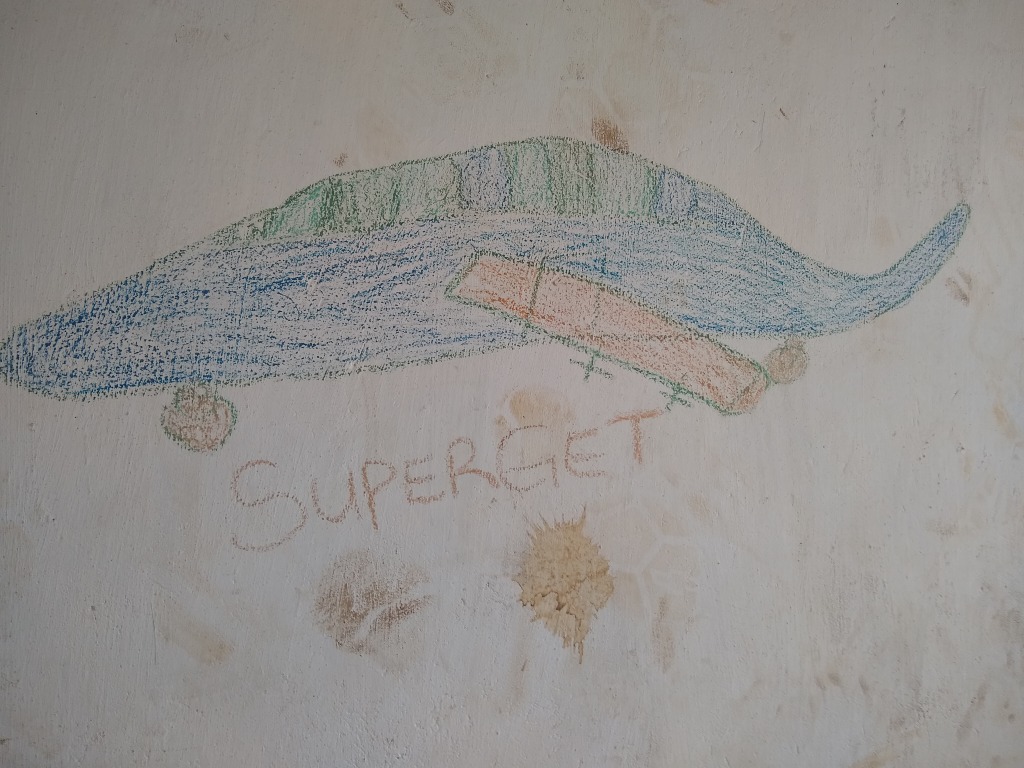

I was impressed by the nursery school students' knowledge of sophisticated military aircraft, but disappointed in their spelling skills.

Adult goat scratching itself

Baby goats

Our goat projects proved to be the most difficult to visit due to their distributed, mobile, mortal nature. But we managed to find pretty much all of them.

Still more goats

Mother goat and similar-looking baby goat.

Goats wandering about in goat-like fashion

I mentioned in passing that I really liked pumpkin and was subsequently presented with five of them to consume as a pre-lunch snack.

Turkey from Mr. Jambo's backyard turkey farm and pumpkin leaves. "You only get turkey once a year in the States, but I can have it whenever I want!"

An excellent, quiet stretch along the river

From the Liwonde bridge

Maloya borehole

Chiyuni borehole

Chamba goat house

Sosola market building

Tiny dried fish seem to be the most in-demand item

Kela borehole

Questionable road for motorcycles

Repairing the chain

Toilet companion

Motorcycle escort

All-day shade

Mua mission

Fancy lodge

One of the few times I didn't have to wade through the swamp

More legit overlanding setup than mine

Mechanic showing off the rope swing

Hipster village beverage

Sunset over Ngala

Mud slog

Still a long way from the lodge

I'll be biking deep into the night, but at least it's pretty!

Creative engineering

Curious locals

Not ADA-compliant

Identity crisis

Taking the tobacco to market

Blending into the mud

Some cultures despise cairns, others turn them into national monuments

One of the more spectacular waterfalls in the world

Boulder-esque ecolodge

Draining into the void

The best thing I ate in Malawi (which bears a remarkable resemblance to everything else I ate here)

Open-air shower with disco ball

Permaculture piglets

Thought about staying in the safari tent, but deterred by threat of local fauna

This bike doctor tried to repair my bike by hitting the gears with a boulder

The Chiyuni nursery school

Yelemiya borehole

Matandala goatlings

Drying cassava

Proceeding down the potato path

Path to the hostel